Home › Forum Online Discussion › General › Japan’s Last Ninja (article)

- This topic has 29 replies, 8 voices, and was last updated 9 years, 4 months ago by

rideforever.

-

AuthorPosts

-

August 19, 2012 at 4:01 pm #39732

A 63-year-old engineer is Japan’s ‘last ninja’

AFPBy Miwa Suzuki | AFP 5 hrs agoA 63-year-old former engineer may not fit the typical image of a dark-clad assassin with deadly weapons who can disappear into a cloud of smoke. But Jinichi Kawakami is reputedly Japan’s last ninja.

As the 21st head of the Ban clan, a line of ninjas that can trace its history back some 500 years, Kawakami is considered by some to be the last living guardian of Japan’s secret spies.

“I think I’m called (the last ninja) as there is probably no other person who learned all the skills that were directly” handed down from ninja masters over the last five centuries, he said.

“Ninjas proper no longer exist,” he said as he demonstrated the tools and techniques used in espionage and sabotage by men fighting for their samurai lords in the feudal Japan of yesteryear.

Nowadays they are confined to fiction or used to promote Iga, some 350 kilometres (220 miles) southwest of Tokyo, a mountain-shrouded city near the ancient imperial capital of Kyoto that was once home to many ninjas.

Kawakami, a former engineer who began teaching ninjutsu — the art of the ninja — ten years ago, said the true history of ninjas was a mystery.

“There are some drawings of their tools but we don’t always find all the details,” which may have been left deliberately vague, Kawakami said.

“Many of their traditions were passed on by word of mouth, so we don’t know what was altered in the process.”

And those skills that have arrived in the 21st century in their entirety are sometimes difficult to verify.

“We can’t try out murder or poisons. Even if we can follow the instructions to make a poison, we can’t try it out,” he said.

Kawakami first encountered the secretive world of ninjas at the age of just six, but has only vague memories of first meeting his master, Masazo Ishida, a man who dressed as a Buddhist monk.

“I kept practising without knowing what I was actually doing. It was much later that I realised I was practising ninjutsu.”

Kawakami said training ranged from physical and mental skills to studies of chemicals, weather and psychology.

“I call ninjutsu comprehensive survival techniques,” though it originated in war skills such as espionage and guerrilla attacks, he said.

“For concentration, I looked at the wick of a candle until I got the feeling that I was actually inside it. I also practised hearing the sound of a needle dropping on the floor,” he said.

He climbed walls, jumped from heights and learned how to mix chemicals to cause explosions and smoke.

“I was also required to endure heat and cold as well as pain and hunger. The training was all tough and painful. It wasn’t fun but I didn’t think much why I was doing it. Training was made to be part of my life.”

Kawakami said he was “a strange boy” growing up but his practice drew little attention at a time when many in Japan were struggling to make ends meet in the hard post-war years.

Just before he turned 19, he inherited the master’s title, along with secret scrolls and special tools.

Kawakami is careful not to claim the title of the “last ninja” for himself and in the sometimes sectarian world of ninjutsu there are doubters and rival claimants, with the disputes centring on the authenticity of various teachings.

Kawakami says much of the ninja’s art lies in catching people unawares, rather than in brute force.

“Humans can’t be on the alert all the time. There is always a moment when they are off guard and you catch it,” he said.

It is all about exploiting weaknesses that allows the ninja to outfox much bigger or more numerous opponents; distracting attention to allow a quick getaway.

It is possible to hide — in a manner of speaking — behind the smallest of things, Kawakami said.

“If you throw a toothpick, people will look that way, giving you the chance to flee.

“We also have a saying that it is possible to escape death by perching on your enemy’s eyelashes; it means you are so close that he cannot see you.”

Kawakami recently began a research job at the state-run Mie University, where he is studying the history of ninjas.

But, he said as he showed an AFP team around the Iga-ryu Ninja Museum and its trick house with hidden ladders, fake doors and an underfloor sword box, he is resigned to the fact that he is the last of his kind.

There will be no 22nd head of the Ban clan because Kawakami has decided not to take on any more apprentices.

“Ninjas just don’t fit in the modern day,” he said.

August 20, 2012 at 1:45 am #39733By Janice WoodAssociate News Editor

Reviewed by John M. Grohol, Psy.D. on August 16, 2012Brain scans show that karate experts have distinctive features in their brains that correlate with punching ability.

The new study from researchers at Imperial College London and University College London found that differences in the structure of white matter the connections between brain regions corresponded with how black belts and novices performed in a test of punching ability.

The researchers note that karate experts are able to generate extremely powerful forces with their punches, but how they do this is not fully understood.

Previous studies have found that the force generated in a karate punch is not determined by muscular strength, which suggests that factors related to the control of muscle movement by the brain might be involved, the scientists said.

Published in the journal Cerebral Cortex, the study looked for differences in brain structure between 12 karate practitioners with a black belt rank and an average of 13.8 years karate experience, and 12 control subjects of similar age who exercised regularly but did not have any martial arts experience.

The researchers tested how powerfully the subjects could punch. To make useful comparisons with the punching of novices, they restricted the task to punching from a short range, a distance of 5 centimeters. The subjects wore infrared markers on their arms and torso to capture the speed of their movements.

As expected, the karate group punched harder, according to the researchers, who explain the power of their punches came down to timing the force they generated correlated with how well the movement of their wrists and shoulders were synchronized.

Brain scans showed that the microscopic structure in certain regions of the brain differed between the two groups. Each brain region is composed of grey matter, consisting of the main bodies of nerve cells, and white matter, which is mainly made up of bundles of fibers that carry signals from one region to another.

The scans used in this study, called diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), detected structural differences in the white matter of parts of the brain called the cerebellum and the primary motor cortex, which are known to be involved in controlling movement, the researchers said.

The differences measured by DTI in the cerebellum correlated with the synchronicity of the subjects wrist and shoulder movements when punching. The DTI signal also correlated with the age at which karate experts began training and their total experience. These findings suggest that the structural differences in the brain are related to the black belts punching ability, according to the researchers.

Most research on how the brain controls movement has been based on examining how diseases can impair motor skills, said neuroscientist Ed Roberts, Ph.D., from the Department of Medicine at Imperial College London, who led the study.

We took a different approach, by looking at what enables experts to perform better than novices in tests of physical skill.

The karate black belts were able to repeatedly coordinate their punching action with a level of coordination that novices cant produce, he continued.

We think that ability might be related to fine tuning of neural connections in the cerebellum, allowing them to synchronize their arm and trunk movements very accurately.

Roberts noted that researchers are just beginning to understand the relationship between brain structure and behavior, but notes his teams findings are consistent with earlier research showing that the cerebellum plays a critical role in the ability to produce complex, coordinated movements.

There are several factors that can affect the DTI signal, so we cant say exactly what features of the white matter these differences correspond to, he said.

Further studies using more advanced techniques will give us a clearer picture.

Source: Imperial College London

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CQRoBRToeY4 (Urban Ninja Free Running – Parkour)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=spzd72_t4g4 (Freddy Krueger Fatalities and Babality)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=us8OhI-OTHg (The Offspring – All I Want)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TFLjF8yp74Q (Oz Gangs – The Aryan Brotherhood)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZJgpnHP10XM (Human Weapon) September 24, 2012 at 6:24 am #39735

September 24, 2012 at 6:24 am #39735The Iga/Koga area thus formed a bridge between the main trade routes from the capital and the vast and wild mountains of the Kii Peninsula to the south. These mountains amaze one even today by the solitude they present for a region so close to the urban sprawl of Osaka and Kyoto. Within these mountains were villagers who lived their entire lives in one tiny valley community shut off from the rest of Japan until comparatively recent times, and visited only by the wandering yamabushi who traversed this wild country on their pilgrimages. Several accounts refer to these mountains as the haunt of bandits who acted highwaymen along the Togaido or as pirates on the sea coast of nearby Ise Province. Many of the ninja myths, such as that of the legendary outlaw Ishikawa Goemon who was supposed to be adept in ninjutsu, no doubt have their origin in the elobaration of the exploits of very un-magical gangs of robbers.

-STEPHEN TURBULL, Ninja AD 1460-1650The Banshenshukai, being the most complete of the texts, is a collection of Ninja knowledge widely regarded as being a complete culmination of Ninja philosophy, military strategy, astrology and weapons. The first thing that strikes one upon reading the text is that it has been largely influenced by Chinese thought as it quotes large sections from Sun Tzu’s Art of War and from various Taoists documents of the era. The rest of the text contains chapters that consists of both diagrams of equipment to be used and matters of Ninja philosophy and strategy. From this and other texts it is clear that the Ninja beliefs and practices were strongly influenced by Chinese mysticism and esoteric knowledge from India and Tibet.

-MARTIN FAULKS, Becoming a Ninja WarriorI perceive fundamental differences in the expression of free will between Mayahana Buddhism, its offshoot in Chan Buddhism, and my investigation of the process underlying Taoist inner alchemy. In my opinion, the Mahayana Buddhists were most likely meditators who realized the falsity, the dead endedness of the mainstream Buddhist teachings and the problems it created – mainly that Emptiness metaphysics destroyed the ground for moral action. If everything is illusory, so is moral action. Plus, they saw that many humans do not resonate with Negative thinking.

Their solution: write up a new text, claim Buddha wrote it on his deathbed, and start a new sect. Was this revelation or cultural realism needed to allow Buddhism to evolve? I say the latter is more likely. Very common in the history of religions for people to invent new levels of Highest Consciousness in order the trump the old order of rellgion and gain adherents. And use the founder of the religion to write the text for them, suddenly (hundreds of years later) clarifying the problem with the original religion. Did the ghost writer of the sutra have super consciousness while He was writing the text? We can tell its not written by a woman, giving birth to form is still bad karma. The superconscious state of mind of the anonymous writer is a matter of belief.

-http://forum.healingdao.com/practice/message/10156/Sorry, but I don’t think that there is anything to admire in committing crimes.

But if I’m allowed to pick let’s say two real person whose activities are quite well known, and who are from some point of view ninja like, would there be better persons than for example Whitey Bulger for sheer ferocity & cunning and Jeffrey Manchester for overall ninja skills?

>>>Kawakami first encountered the secretive world of ninjas at the age of just six, but has only vague memories of first meeting his master, Masazo Ishida, a man who dressed as a Buddhist monk>>>

This is dangerous aspect with Buddhadharma, because rationalized good can be rationalized also other way around.

HOWDY

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nrlKyDIx91o (kujikiri)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WD-OZI7NdpY (shinobimystic)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fiFB5kxNpxY (chosunninja)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SE3vZQnAgQk (cheerleaders)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rk0gVJ_Bdns (stephenkhayes)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0MVyNbfa-G4 (trackingsurvival) September 26, 2012 at 4:24 am #39737September 26, 2012 at 10:54 am #39739September 27, 2012 at 7:20 am #39741November 14, 2012 at 5:25 am #39743

September 26, 2012 at 4:24 am #39737September 26, 2012 at 10:54 am #39739September 27, 2012 at 7:20 am #39741November 14, 2012 at 5:25 am #39743Greetings

It is not in my nature to get involved with other peoples statements. It is their life and reality, but in this claim, I must reply – Maybe this man trained Ryu’s of ninjutsu and that is fine, but he is not the last ninja in Japan.

Please look at Hatsumi Masaaki’s Bujinkan organisation. There are 9 Ryu’s to be taught.This is not a battle “who is right or better”, just a correction.

Sincerly

Steffen Nielsen, DenmarkNovember 24, 2012 at 5:25 am #39745Oriental prototype of the cloak-and-dagger man.

THE NINJA

W. M. Trengrouse

What cowboys have been to U.S. entertainment, the Ninja — the stealers in — are in contemporary Japan. But a Ninja is less like a cowboy than a dirty-dealing Superman. Originally a medieval cult of unconventional warrior-spies, as presented in the vogue now sweeping Japan from toddlers to grandparents they have the power to turn themselves into stones or toads, are as invisibly ubiquitous as gremlins, and can do things like jumping ten-foot walls and walking on water.

Television carries Ninja dramas from morning until night, kabuki and the serious stage put on Ninja plays, eighteen Ninja movies were made in 1963 and 1964, bookstores carry two hundred fiction and non-fiction titles on the occult art, children’s comic books and the adult pulps are loaded with their adventures, toy stores sell Ninja masks and weapons, and even Kellogg’s corn flakes has a Ninja mask on the box. It has got to the point that kindergarten classes have been asked to pledge they will not play Ninja, the police are plagued by moppet bands of Ninja, and hardly a castle wall in Japan has not been attacked by amateur Ninja scalers.

The legend of the stealers — in as much a part of Japanese culture as Robin Hood and King Arthur are of the English — has a reasonably firm if little researched basis in history, and its artifacts can be seen even today. The supernatural powers of the popular Ninja character are only an exaggeration of some remarkable accomplishments of his prototype, some of them strangely similar to things we regard as peculiarly modern. The Ninja did practice the art of invisibility — ninjutsu — through choice of clothes and other quite natural means. The inventions they used in their profession anticipated the skin diver’s snorkel and fins, the collapsible boat, K-rations, the four-pronged scatter spike for traffic sabotage, tactical rockets, and water skis.

Origins

The Ninja most probably began with a group of “mountain ascetics” who lived in the hills around Kyoto and Nara when those towns were the capitals of Japan and Buddhism was being established. The Ninja beliefs and practices show the influence of Buddhism (with a mixture of Shinto), of the Chinese way of hand fighting, and of the ancient writings of the Chinese Sun Tzu, with his emphasis on spies and on stratagems, deception operations.1 By the end of the Nara period (710-784) this cult of mountaineers (Yama-bushi, those who sleep among the mountains), who were “men of lower caste representing the crude side of religion, … exercised a great influence upon the people by appealing directly to vulgar ideas and superstitions.”2 Occult and dreaded, they lived and taught their blend of Buddhism (mainly of the Tendai and Shingon sects, the latter dealing in mystic hymns and secret formulas) and Shinto on such mountains as Koya and Hiei. They inducted young men into their secret orders, and they came down to the villages to get contributions in return for doing magical cures through formulas and medicines.But their miracles were not enough to protect them in the face of government hostility to the cult, and the priests turned to guerrilla warfare, versing themselves in what was to become bujutsu, the martial art of eighteen methods — karate, bojutsu, kenjutsu, and so on — to protect their shrines and temples. These had been established twenty miles to the east of Nara at Iga-Ueno, then a farming village situated on a broad tableland rimmed by mountains. The area was so poor and isolated that it was not deemed worth fighting for by the warring landlords of Nara and Kyoto, and so it went by default to the mountaineer cult. Here ninjutsu became an independent art.

Before the end of the Heian period (794-1185), the first book treating ninjutsu appeared, written by the great Genji warrior Yoshitsune Minamoto (1159-1189), the “Book of Eight Styles of Kurama.” Mt. Kurama, a training station of the mountain ascetics, was where Yoshitsune mastered his arts as a child. This book emphasizes the art of flying — Yoshitsune is believed to have been a great jumper — and the use of shock troops. It first distinguished among the three arts of strategy, bujutsu, and ninjutsu. Although ninjutsu was still embryonic, it was established as an art by Yoshitsune’s “book of ninjutsu,” so referred to and extant today.

The Iga area was so impoverished that families often killed their children, particularly girls, and they could not get their whole livelihood from farming. On the other hand adults, or any who could perform adult labor, were valuable. Warfare in the plains of Iga therefore tended to be carried on by stealth rather than by bloodshed. The mountain priests would teach the head of a strong family their secret arts, and these would be passed from a father to his sons, who might also visit the wilderness temples for indoctrination. Even today, says playwright-novelist Tomoyoshi Murayama, the people of Iga are known as sly, tricky, and crafty.

Three grades of Ninja sprang up — the jonin (leader), who was head of a strong family, the chunin (middle class), a skilled Ninja, and the genin (lowest), a day laborer in ninjutsu. As the people of Iga became known for Ninja, fighting landlords in the period of the civil wars from the middle of the fourteenth to the end of the sixteenth century called upon the town for spies and warriors. There were two major families there, each having about three hundred Ninja. In addition, another settlement at Koga, some twelve miles away, had fifty-three families of roughly equal rank with a smaller number of Ninja. The heads of the Iga forces were jonin, those in Koga only chunin.

Masashige Kusunoki, the warrior genius of the latter part of the 14th century, is regarded as the father of advanced ninjutsu. Like Yoshitsune Minamoto, he had learned the basics of the science from mountain ascetics as a child, but unlike him used Ninja not only for attack but also for defense and peacetime purposes. According to Iga historian Heishichiro Okuse, he had forty-eight Ninja under him who spied in Kyoto, Osaka, and Kobe. One of his exploits, reducing an impregnable fortress, was accomplished by locating the enemy’s supply route, killing the bearers, dressing his Ninja in their armor, and sending them on, bearing bags of arms. When the gates swung open the Ninja struck and set fire to the castle. On another occasion, after vainly trying to defend his castle from attack, he was found dead in his armor by the attackers, his personal Ninja crying over the body. But while the enemy were celebrating their triumph, Kusunoki, who of course had only been feigning death, arose and crushed them.

“Two Hundred Techniques”3

The Ninja’s garb was all black. He wore a black cloth wrapped in turban style about his head and covering his mouth and jaw. His cloak was full-sleeved, and the arms ended in gauntlets. Chain mesh armor was often worn beneath it. The pants were baggy, tied above the ankle. Even the socks (tabi) and sandals (zori) were black, with cotton padding on the bottom of the zori for stealthy walking. The clothes were filled with hidden pockets.The traditional samurai sword was often shortened to leave room in the bottom of the scabbard for poisonous dust or blinding-powder which could be hurled into an enemy’s face. The hilt was likely to be square across, with a long light cord attached, so that the sword could be leaned against a wall as a first step in scaling and then pulled up afterwards.

In traveling, the Ninja usually carried the following equipment: a straw hood for covering his face except for small holes to see through; a rope and hook for climbing; a stone pen for writing on walls; medical and food pills (including hydrogen pellets a half inch in diameter made of carrot extract, soda powder, wheat flour, mountain potatoes, herbs, and rice powder–two or three a day would sustain the Ninja for ten days); thirst-allaying tablets made of palm fruit, sugar, and barley; medicine to prevent frozen fingers; a lighter flint; and a black three-foot towel which could be used in climbing, to hide the face, or to carry water purifiers or poison absorbed from secret mixtures into which its ends had been dipped.

One type of weapon was shuriken, missiles which he could hurl with pinpoint accuracy for thirty feet. Usually he had nine of these, either metal knives six or so inches long or disks in the shape of stars, comets, swastikas, or crosses. Another was the bamboo pole fitted with a hook for climbing or with a balled chain for attack. More subtle were hollowed eggs containing dried jellyfish, toads’ eggs, powdered snake grass, and powdered leaves from a “sneeze tree”; these were thrown to blind or unnerve his opponent. Water guns, to be shot from up wind only, were loaded with a deadly three-second poison.

There were poison rings utilizing the all-powerful tiger’s nail, and leather gloves (shuko) were tipped with iron cat’s claws for climbing, raking a face, or fending off a sword.

The Ninja had the secret of gunpowder before it was generally known in Japan. They developed wooden cannons, designed grenades and time bombs, mounted incendiaries on arrows, and tipped arrows with leaf-like ends to scatter the fire. As anti-personnel weapons against their soft-shod enemies they scattered sharp-pointed nuts, iron tripods with needle points, and solid pyramids of metal which would fall upright.

There were two types of water shoes. One was a wooden circle three feet in diameter with a center of solid board, the other simply two buckets, with a wooden fan on a bamboo pole used as a paddle. For invisible swimming the Ninja used bamboo tubes as snorkels, wooden fins for speed and silence. The snorkel sometimes had one enlarged end and could double as a horn or a blowgun. Their collapsible boat folded on its hinges to the size of a filing drawer. In use it would be caulked with sap. They also used rabbit skin to make floats of the Mae West type.

The Ninja are credited with developing a secret walk which would take them along at twelve miles an hour with less effort than ordinary mortals make for four; but this secret, if they had it, has been lost. They did use a crab-like walk, crossing one foot over the other and moving sideways, for walls and narrow passages.

They were well versed in nature lore. To get his direction in the dark a Ninja would pull up a radish; the side with more root fibers points south. To find the depth of water in a moat he would pull a reed toward him (they can’t be pulled up by the roots) and calculate by a sort of empirical Pythagorean geometry from the submerged increment per displacement from the vertical. From a cat’s eyes he could read time with the help of a song into which the formula was woven. He watched the tides, currents, constellations, the moon and sun, the winds, and the colors of the sky to forecast the weather and the best moment to strike (there was another song on the dates of currents). A thin sheet of iron heated and then cooled at rest could be floated in water to form a crude compass.

A study of snores observed with a bamboo listening pipe told the Ninja the sleep status of their victims. They learned to boil rice without a pot (wrapping it in a wet straw sack, burying it in the ground, and building a fire on top) and freshen salt water (by packing red earth on the bottom of the boat to absorb the salt). A wooden fan was used as a protractor to measure angles and thereby determine distances. They had their own secret ideographs and coded call signs. They were adept at “Gojo no Ri,” the ability to read their opponent’s mind and mood from facial indications, voice, gesture, etc.

The Ninja used many disguises, but it is said there were seven basic covers–the priest, perhaps offering prayers for the enemy dead while making a head count of the quick and a general survey of their battlefields, the mountain ascetic who could spy from above and signal by conch shell from mountain top to mountain top, the itinerant merchant who could be admitted to castles, the wandering bard and the entertainer with their songs and tricks, and the commoner.

The mystical elements of ninjutsu, largely from the Shingon sect, took the form of secret hand signs and murmured formulas. The art of invisibility and transformation is also put in mystical terms. Shugendo, the mountain ascetic creed, says, “Conceive that you are a stone.” If you believe you are a stone, then you are. It is much like becoming one with Buddha. When the Ninja is surrounded by enemies and has no place to escape, he shortens his breath, shrinks himself as small as a stone and conceives he is a stone. The enemy cannot find him.

This particular camouflage is called Doton no jutsu, invisibility by means of the earth. But four other elements can be used. In Katon no jutsu a man is turned into smoke (helped by liberal use of gunpowder in the Ninja practice of blowing one’s face off to preserve secrecy when cornered). But this probably refers primarily to the use of smoke screens, setting fire to infiltrated castles, etc. Suiton no jutsu is making use of water to disappear, likely with a snorkel. Mokuton no jutsu is to hide in trees. And Kinton no jutsu is the use of metal; Ninja would crawl into rice boilers, hanging bells, and temple statuary to spy. A combination of metal and water was to steal a large temple bell and jump into deep water with it, making use both of its weight and of its trapped air supply.

Mass Action and Decline

The last burst of Ninja activity came under Ieyasu Tokugawa (1541-1616), who was to become the first shogun of a unified Japan. On February 6th, 1562, the general wrote a letter of gratitude to a Koga Ninja, Yoshichiro Ban, for services rendered two years before Ieyasu had had to attack an impregnable castle (we gather all castles were impregnable until the Ninja were called in) and had asked Ban to lead 280 Ninja in an infiltration movement. This band slipped in at night and fired the castle towers. The defenders thought their own men had betrayed them and fell into confusion. The Ninja totally disrupted them without use of staff or sword except to behead the enemy leader.Two other generals, however, who helped in the unification of the country, Nobunaga Oda (1534-1582) and Hideyoshi Toyotomi (1536-1598), were trying to stamp out Buddhism and therefore not only rebuffed but held and tortured any Ninja who fell into their hands. In 1581, 9000 of Oda’s men attacked a force of 4000 men from Iga, including many Ninja, laid waste the town, and slaughtered its warriors. Ninja leader Hanzo Hattori, lamenting the death of his townsmen, asked Ieyasu to employ the survivors, and the great general did. Then in the battle of Sekigahara (1600), 100 Ninja of the 200 in the Ieyasu forces were killed.

In the first years of the 17th century, when Ieyasu as shogun moved the political capital of the country to Edo (Tokyo), he took 200 Ninja with him. He made Hanzo and his successors the equivalent of U.S. Secret Service chiefs. The Ninja had complete and unquestioned access to the shogun to protect and inform him. (The main west entrance to the Imperial Palace, then the shogun’s residence, is still called Hanzo’s gate, and parts of Tokyo where the Ninja lived are now named Koga-cho, Iga-cho, and Kogai-cho.) Their cover was gardener employment, and they lived it. But they were always ready to be stopped among the poppies with the order, “Go to Kyoto,” and they would drop their spades and set out at once at Ninja speed.

In 1638, when farmers and Christians in Shimabara, Kyushu, rebelled against the shogunate, Ninja were called in again, this time strictly to gather information. The fight had lasted ten months, and 40,000 rebels were holding the Shimabara castle (impregnable) against 130,000 of Ieyasu’s troops. Finally the commanding general, Nobutsuna Matsudaira, ordered ten Ninja to reconnoiter the castle. “We have no idea of the layout inside the enemy camp,” he said. “Determine the depth and width of the moat, the height of the wall and fence, and the distance from our camp to theirs; and draw a map.”

Five Ninja fired guns as a diversion. After the consequent enemy stir had subsided, at midnight, the Ninja moved in from the opposite side, scaling the castle wall with rope ladders. Two of them fell into traps in the floor, and this aroused the guards. Nevertheless the Ninja, with their black garb and ability to work in the dark, accomplished their mission, and they carried off the enemy’s cross-bearing flag as well.

With the coming of peace, however, the Ninjas, like old generals, now faded into the administrative spy and other dull professions. The era of the true Ninja was over.

——————————————————————————–

1 For example: “In the whole army none should be more favorably regarded than the spies; none should be more liberally rewarded than the spies …” And elsewhere, “A stratagem is a military trick. You should win the enemy to your side … throw him into confusion … break his unity by provocation … make him overconfident and relax his guard …”

2 Masaharu Anesaki, History of Japanese Religion.

3 Most of the information in this section is taken from the 22-volume Bansen Shukai (Thousands of Rivers Gather in the Sea), written in 1674 by Natsutake Fujibayashi. Extant in seven manuscript copies, it is now being edited for publication. Notable among the score or more of other 17th- and 18th-century accounts of ninjutsu is the volume Shonin-ki (The True Ninjutsu).

November 24, 2012 at 5:42 am #39747

November 24, 2012 at 5:42 am #39747Japan’s ninjas heading for extinction By Mariko Oi

Tools of a dying artFive nearly-true ninja myths

Ninjutsu is a martial art: In fact, fighting was a last resort – ninjas were skilled in espionage and defeating foes using intelligence, while swinging a sword was deemed a lower art

Ninjas could disappear: They couldn’t vanish as they do in the movies, but being skilled with explosives, they could make smoke bombs to momentarily misdirect the gaze, then flit away

They wore black: Ninja clothing was made to be light and hard to see in the dark – but jet-black would cause the form to stand out in moonlight, so a dark navy blue dye was usually used

Ninjas could fly: They moved quietly and swiftly, thanks to breathing techniques which increased oxygen intake, but kept their feet on the ground

And walk on water: CIA intelligence says they used “water shoes” – circular wooden boards or buckets – and a bamboo paddle for propulsion, but doubt remains over their effectiveness

Source: Iga-Ryu Ninja Museum

However, ninjas did apparently have floats that enabled them move across water in a standing position.Western ninja-inspired nonsense

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: This comic-book sewer-dwelling quartet evolved into talking, pizza-eating humanoids named after Italian artists – they inspired a toy craze, film and video game

American Ninja: 1985 film with Michael Dudikoff as GI Joe Armstrong, whose platoon is killed by ninjas in the Philippines – when they kidnap the colonel’s daughter he saves her thanks to his own extraordinary ninjutsu skills

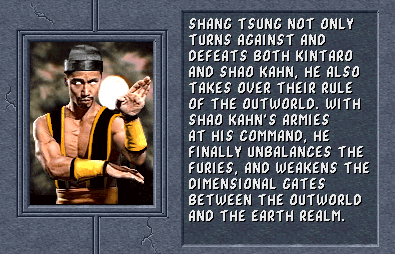

Mortal Kombat: Arcade and console series so gory it prompted the US to adopt age-ratings for games – characters had “special moves”, like Sub-Zero’s ability to generate ice to freeze opponentsJapan’s era of shoguns and samurai is long over, but the country does have one, or maybe two, surviving ninjas. Experts in the dark arts of espionage and silent assassination, ninjas passed skills from father to son – but today’s say they will be the last.

Japan’s ninjas were all about mystery. Hired by noble samurai warriors to spy, sabotage and kill, their dark outfits usually covered everything but their eyes, leaving them virtually invisible in shadow – until they struck.

Using weapons such as shuriken, a sharpened star-shaped projectile, and the fukiya blowpipe, they were silent but deadly.

Ninjas were also famed swordsmen. They used their weapons not just to kill but to help them climb stone walls, to sneak into a castle or observe their enemies.

Most of their missions were secret so there are very few official documents detailing their activities. Their tools and methods were passed down for generations by word of mouth.

This has allowed filmmakers, novelists and comic artists to use their wild imagination.

Hollywood movies such as Enter the Ninja and American Ninja portray them as superhumans who could run on water or disappear in the blink of an eye.

“That is impossible because no matter how much you train, ninjas were people,” laughs Jinichi Kawakami, Japan’s last ninja grandmaster, according to the Iga-ryu ninja museum.

Kawakami is the 21st head of the Ban family, one of 53 that made up the Koka ninja clan. He started learning ninjutsu (ninja techniques) when he was six, from his master, Masazo Ishida.

“I thought we were just playing and didn’t think I was learning ninjutsu,” he says.

“I even wondered if he was training me to be a thief because he taught me how to walk quietly and how to break into a house.”

Other skills that he mastered include making explosives and mixing medicines.

“I can still mix some herbs to create poison which doesn’t necessarily kill but can make one believe that they have a contagious disease,” he says.

Kawakami inherited the clan’s ancient scrolls when he was 18.

While it was common for these skills to be passed down from father to son, many young men were also adopted into the ninja clans.

There were at least 49 of these but Mr Kawakami’s Koka clan and the neighbouring Iga clan remain two of the most famous thanks to their work for powerful feudal lords such as Ieyasu Tokugawa – who united Japan after centuries of civil wars when he won the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600.

It is during the Tokugawa era – known as Edo – when official documents make brief references to ninjas’ activities.

“They weren’t just killers like some people believe from the movies,” says Kawakami.

In fact, they had day jobs. “Because you cannot make a living being a ninja,” he laughs.

Kawakami demonstrates ninja techniques

There are many theories about these day jobs. Some ninjas are believed to have been farmers, and others pedlars who used their day jobs to spy.“We believe some became samurai during the Edo period,” says Kawakami. “They had to be categorised under the four caste classes set by the Tokugawa government: warrior, farmers, artisan and merchants.”

As for the 21st Century ninja, Kawakami is a trained engineer. In his suit, he looks like any other Japanese businessman.

The title of “Japan’s last ninja”, however, may not be his alone. Eighty-year-old Masaaki Hatsumi says he is the leader of another surviving ninja clan – the Togakure clan.

Hatsumi is the founder of an international martial arts organisation called Bujinkan, with more than 300,000 trainees worldwide.

“They include military and police personnel abroad,” he tells me at one of his training halls, known as dojo, in the town of Noda in Chiba prefecture.

It is a small town and not a place you would expect to see many foreigners. But the dojo, big enough for 48 tatami mats, is full of trainees who are glued to every move that Hatsumi makes. His actions are not big, occasionally with some weapons, but mainly barehanded.

Hatsumi explains to his pupils how those small moves can be used to take enemies out.

Paul Harper from the UK is one of many dedicated followers. For a quarter of a century, he has been coming to Hatsumi for a few weeks of lessons every year.

“Back in the early 80s, there were various martial art magazines and I was studying Karate at the time and I came across some articles about Bujinkan,” he says.

“This looked much more complex and a complete form of martial arts where all facets were covered so I wanted to expand my experience.”

Harper says his master’s ninja heritage interested him at the start but “when you come to understand how the training and techniques of Bujinkan work, the ninja heritage became much less important”.

Hatsumi’s reputation doesn’t stop there. He has contributed to countless films as a martial arts adviser, including the James Bond film You Only Live Twice, and continues to practise ninja techniques.

Both Kawakami and Hatsumi are united on one point. Neither will appoint anyone to take over as the next ninja grandmaster.

“In the age of civil wars or during the Edo period, ninjas’ abilities to spy and kill, or mix medicine may have been useful,” Kawakami says.

“But we now have guns, the internet and much better medicines, so the art of ninjutsu has no place in the modern age.”

As a result, he has decided not to take a protege. He simply teaches ninja history part-time at Mie University.

Despite having so many pupils, Mr Hatsumi, too, has decided not to select an heir.

“My students will continue to practice some of the techniques that were used by ninjas, but [a person] must be destined to succeed the clan.” There is no such person, he says.

The ninjas will not be forgotten. But the once-feared secret assassins are now remembered chiefly through fictional characters in cartoons, movies and computer games, or as a tourist attractions.

The museum in the city of Iga welcomes visitors from across the world where a trained group, called Ashura, entertains them with an hourly performance of ninja tricks.

Unlike the silent art of ninjutsu, the shows that school children and foreign visitors watch today are loud and exciting. The mystery has gone even before the last ninja has died.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-20135674

January 11, 2013 at 7:44 am #39749January 11, 2013 at 3:31 pm #39751

January 11, 2013 at 7:44 am #39749January 11, 2013 at 3:31 pm #39751(In the first years of the 17th century, when Ieyasu as shogun moved the political capital of the country to Edo (Tokyo), he took 200 Ninja with him. He made Hanzo and his successors the equivalent of U.S. Secret Service chiefs. The Ninja had complete and unquestioned access to the shogun to protect and inform him.)

Tokugawa Ieyasu was BRILLIANT, he completely nullified the threat from ninja by making them company men. He operated from a beautiful yin state resulting from one experience of pushing against the natural flow. Ieyasu was almost killed while leading a horse brigade after Takeda Shingen… so terrified that he actually peed and pooped his pants…finally reaching the safety of his castle, Ieyasu immediately had an artist draw an image of his horrified face. This picture he constantly carried on himself, pulled it out whenever he felt that impatience was pulling him off from the Tao. This was when he was about 19yo and he didn’t become shogun until he was about 64yo (he abdicated shogun to his son within 2 years). That is an incredible wait in that era, most people died at 40.

Tried to paste a copy of the picture here but can’t figure out how to 🙁

January 11, 2013 at 5:44 pm #39753you put the web address of the picture

you want inserted into the section below

the text area called “Insert Image”January 11, 2013 at 8:53 pm #39755January 11, 2013 at 8:54 pm #39757January 11, 2013 at 8:54 pm #39759 -

AuthorPosts

You must be logged in to reply to this topic.