Home › Forum Online Discussion › General › Number Of Super-Centenarians (110+ Years Of Age) Vastly Declines

- This topic has 5 replies, 2 voices, and was last updated 6 years, 2 months ago by

c_howdy.

-

AuthorPosts

-

August 16, 2019 at 5:44 pm #58931

Is It Time To Throw Away Your Anti-aging Pills

Now That There Is Only A Remote Possibility

Of Living 120 Healthy Years?Estimated Number Of Super-Centenarians (110+ Years Of Age)

Vastly Declines Once Birth Certificates Are Used For ConfirmationBy Bill Sardi

In this “aging is optional” era, with many middle-age longevity seekers eyeing the prospect of living 120 healthy years, a newly published study says the possibility of living that long is remote. So, shall longevity seekers throw away their anti-aging pills and save their money?

In a world of “fake news” it is not surprising to learn that the reported number of super-centenarians (110+ years of age) around the world, concentrated in so-called “blue zones” around the globe (Okinawa, Japan; Ikaria in Greece; the isle of Sardinia near Italy), are largely comprised of oldsters with no birth certificates to prove they have lived eleven decades and/or whose families have not reported their deaths in order to maintain delivery of government retirement checks.

According to a published report, super-centenarians almost don’t exist once birth certificates are used to validate longevity in the US. Census, baptismal and passport records are often used in lieu of birth certificates, especially in remote areas of the world where literacy rates are low. The report states the number of supercentenarians (110+ years of age) in the US is vastly over-estimated by 69-82% once birth certificates are demanded as proof of birth date.

A report published in 2010 in the Journal of the American Geriatric Society noted that the US census in 2000 listed 1400 supercentenarians (about 1 per 200,000) while a more rigorous investigation by the Gerontology Research Group determined just 60-70 living Americans have survived to age 110 or longer (1 super-centenarian per 6 million people).

But over-reporting of the number of super-centenarians in the US has been known for some time. Historically the US doesn’t have a good birth record keeping history as does Japan where prefectures have kept family records for decades. A recent report compared the US super-centenarian figures with Italy which keeps more accurate birth records. But even Italian data “supports the hypothesis that these semi-super-centenarians largely constitute a collection of age reporting errors.”

And even in Japan where birth records are fastidiously kept, an investigation found 238,000 centenarians were dead or missing, leaving just 40,399 with known addresses.

Are modern longevity seekers chasing the wind?

And it’s not just the lack of birth records, it’s actual fraud as families of longevinarians don’t report the death of their loved ones so government pension checks continue to be delivered. The reportedly oldest living human in modern times, Jean Calment of France who reportedly lived 122 years was actually replaced by her 99-year-old daughter, just for that reason.

So, what does this report mean to all the people who are attempting to live much, much longer, by taking an anti-aging pill? According to a report published at LiveScience.com, it means the chance of living to age 110 years and beyond just shrunk from about 2 in 1000 to 1 in 1000. But don’t throw away your anti-aging pills just yet.

The report, published in BioRViv, says the so-called “blue zones” around the globe where super-centenarians are reported to abound are regions of low life expectancy, low income, low rates of literacy, high crime rates and poor health. So, investigators think there is something “fishy” going on with the data.

But one would expect a sub-group of people in low income areas to live longer if food is not abundant, under the well-founded premise that eating fewer calories can add decades to a person’s life. That is precisely what is happening in Cuba (more about this below).

Calorie restriction has been shown to double the lifespan of laboratory animals. That equates with eating about one meal a day in human terms. However, not many are expected to join the Calorie Restriction (food deprivation) Society. Molecules like resveratrol (rez-vair-a-trol) that mimic a calorie-restricted diet are in order.

Investigators want to know why would super-longevity occur in a population where there is poor life expectancy overall? Keep reading.

These “blue zones” that are characterized as low-income/ low literacy areas with poor life expectancy in general are in stark contrast to the geographic differences in life expectancy in the US. For example, people who live in an impoverished area of St. Paul, Minnesota have a life expectancy of ~65 years while a nearby wealthy district has a life expectancy of 86 years — a 21-year difference! Education, income and poor nutrition explain this difference.

Forbes.com reports the life expectancy in parts of Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas is around 66 years, about the same as found in backward 3rd world countries of Burma and Ghana.

These geographical differences in life expectancy can be skewed by opioid drug or tobacco use that is often prevalent in impoverished areas. Smokers die about a decade sooner than non-smokers.

But in Cuba, where public salaries are about $30/month and food shortages abound as calorie-restricted diets are not optional, there are an estimated 2070 centenarians out of a population of 11.2 million. That’s almost 2 centenarians for every 1000 Cubans. Impoverishment can have its advantages. Life expectancy for the population at large in Cuba is 79.5 years.

The same goes for Okinawa, the southern-most island of Japan, whose economy lagged behind that of the rest of the country. Extreme poverty and starvation comprise the modern history of Okinawa. What followed was an upsurge in the number of centenarians. (100+ years) in Okinawa.

As incomes have risen and processed foods consumed in greater quantity, the “Okinawa Effect” has begun to vanish. The younger generation living on Okinawa have opted for American fast food and Okinawa no longer holds the top spot for life expectancy among Japan’s 47 prefectures.

The reason why life expectancy is relatively low in impoverished areas of the US compared to similar low income areas in Cuba and Okinawa may be these overseas populations have traditionally grown their own food.

Fast food outlets predominate in American communities with low incomes. But according to a recent report, fast food is often too expensive for low income families and is not consumed more frequently by low income groups than upper income groups. It’s a diet of Cokes and Oreos at home, providing what Dr. Derrick Lonsdale calls “high calorie malnutrition.”

The lack of abundant food makes it difficult to overeat. For example, the Cuban calorie intake has reportedly declined from ~3000 calories per day down to ~1800 calories per day over recent times.

Being forced to grow your own food would certainly limit food intake. But growing your own food may not be an easy option in St. Paul, Minnesota, particularly in winter months. Low-income adults living in the St. Paul area are far less likely to be growing their own food and opt for processed foods and empty calories (Cheerios, boxed macaroni and cheese, sugarized or synthetically sweetened beverages) than people living on the isle of Okinawa or in Cuba.

How might we know the success of our efforts to delay aging?

How would a person know they are prematurely aging? According to one survey, the most prevalent physical markers of super-centenarians are cataracts (88%), osteoporosis/bone loss (44%) and high blood pressure (22%). Delaying the onset of these conditions would be a marker of biological youthfulness.

For example, the average age of the surgical cataract patient is the US today is just under 70 years. Given that the natural focusing lens of the human eye gradually loses its focusing power (need for reading glasses typically occurs around age 40) and loses about 1% of its transparency with every year of life, it is inevitable as people live longer they will need to have a cloudy lens surgically removed and a clear plastic lens implanted in its place.

Cataracts are a marker of mortality risk. However, attempts to delay or live with cloudy cataracts over unfounded fear of eye surgery also increases the risk for death. Cataract surgery actually lessens the death risk.

While some fearful senior Americans delay cataract surgery to their own demise (face loss of their driver’s license, experience falls and accidents), a few retirees maintain clear lenses into their nineties. Cataracts are a good marker of aging.

It is not surprising to learn that resveratrol, known as an anti-aging molecule, raises levels of glutathione, a strong natural antioxidant produced in the lens of the eyes that maintains its clarity.

What now?

OK, you want to live 120 healthy years and you are taking an anti-aging pill in hopes of adding 3 or 4 decades to your lifespan. Longevity seekers have to wade through their eighties and nineties while they suffer bone loss (osteoporosis) and muscle deterioration (sarcopenia) and have cloudy cataracts removed to maintain functional eyesight in that quest. Or do they? In the animal lab resveratrol, known as an anti-aging molecule, has exerted a powerful effect in delaying or even reversing bone loss and muscle shrinkage. There is no comparable drug that does this.

Population data does not apply to individuals

With the news that super-longevity appears to be a remote possibility, have the hopes of many longevity seekers just been dashed?

Before you throw out your anti-aging pills, just precisely how do those population numbers, based upon people who just happen to have lived extra-long lives by chance, without consciously trying, have anything to do with today’s modern longevity seekers who are intentionally practicing intermittent fasting, or adhering to a ketogenic (low carbohydrate) diet and/or taking resveratrol pills?

Group data applies to groups, not individuals. Moving your residence into one of these “red zones” where life expectancy is shortened would not necessarily cut your life short either.

Will this latest report that claims the chance of living 110-years and beyond is only a remote possibility going to cause longevity seekers to throw away their resveratrol pills? The latest report has no relevance to providing an answer to that question. Because people who don’t take an anti-aging pill and are not consciously practicing any anti-aging measures only have a miniscule chance of living 110+ years is not germane to whether anti-aging pills are efficacious or not. But you can bet that resveratrol pill users will be ridiculed for wasting their money on what will be called a false promise.

The longevity seekers of today won’t know the outcome of their personal quest for a super-long life until they have lived to their 110th birthday. Conclusive evidence that anti-aging pills actually work requires decades to materialize. Anti-aging pill users are betting on existing scientific studies that are presumed to apply to humans. Staunch anti-aging pill users are not likely to be dissuaded from their pursuit of super-longevity.

August 24, 2019 at 7:18 am #58950How memories form and fade

by Lori Dajose, California Institute of Technology

Why is it that you can remember the name of your childhood best friend that you haven’t seen in years yet easily forget the name of a person you just met a moment ago? In other words, why are some memories stable over decades, while others fade within minutes?

Using mouse models, Caltech researchers have now determined that strong, stable memories are encoded by “teams” of neuronsall firing in synchrony, providing redundancy that enables these memories to persist over time. The research has implications for understanding how memory might be affected after brain damage, such as by strokes or Alzheimer’s disease.

The work was done in the laboratory of Carlos Lois, research professor of biology, and is described in a paper that appears in the August 23 of the journal Science. Lois is also an affiliated faculty member of the Tianqiao and Chrissy Chen Institute for Neuroscience at Caltech.

Led by postdoctoral scholar Walter Gonzalez, the team developed a test to examine mice’s neural activity as they learn about and remember a new place. In the test, a mouse was placed in a straight enclosure, about 5 feet long with white walls. Unique symbols marked different locations along the walls—for example, a bold plus sign near the right-most end and an angled slash near the center. Sugar water (a treat for mice) was placed at either end of the track. While the mouse explored, the researchers measured the activity of specific neurons in the mouse hippocampus (the region of the brain where new memories are formed) that are known to encode for places.

When an animal was initially placed in the track, it was unsure of what to do and wandered left and right until it came across the sugar water. In these cases, single neurons were activated when the mouse took notice of a symbol on the wall. But over multiple experiences with the track, the mouse became familiar with it and remembered the locations of the sugar. As the mouse became more familiar, more and more neurons were activated in synchrony by seeing each symbol on the wall. Essentially, the mouse was recognizing where it was with respect to each unique symbol.

To study how memories fade over time, the researchers then withheld the mice from the track for up to 20 days. Upon returning to the track after this break, mice that had formed strong memories encoded by higher numbers of neurons remembered the task quickly. Even though some neurons showed different activity, the mouse’s memory of the track was clearly identifiable when analyzing the activity of large groups of neurons. In other words, using groups of neurons enables the brain to have redundancy and still recall memories even if some of the original neurons fall silent or are damaged.

Gonzalez explains: “Imagine you have a long and complicated story to tell. In order to preserve the story, you could tell it to five of your friends and then occasionally get together with all of them to re-tell the story and help each other fill in any gaps that an individual had forgotten. Additionally, each time you re-tell the story, you could bring new friends to learn and therefore help preserve it and strengthen the memory. In an analogous way, your own neurons help each other out to encode memories that will persist over time.”

Memory is so fundamental to human behavior that any impairment to memory can severely impact our daily life. Memory loss that occurs as part of normal aging can be a significant handicap for senior citizens. Moreover, memory loss caused by several diseases, most notably Alzheimer’s, has devastating consequences that can interfere with the most basic routines including recognizing relatives or remembering the way back home. This work suggests that memories might fade more rapidly as we age because a memory is encoded by fewer neurons, and if any of these neurons fail, the memory is lost. The study suggests that one day, designing treatments that could boost the recruitment of a higher number of neurons to encode a memory could help prevent memory loss.

“For years, people have known that the more you practice an action, the better chance that you will remember it later,” says Lois. “We now think that this is likely, because the more you practice an action, the higher the number of neurons that are encoding the action. The conventional theories about memory storage postulate that making a memory more stable requires the strengthening of the connections to an individual neuron. Our results suggest that increasing the number of neurons that encode the same memory enables the memory to persist for longer.”

The paper is titled “Persistence of neuronal representations through time and damage in the hippocampus.”

More information: “Persistence of neuronal representations through time and damage in the hippocampus” Science (2019). science.sciencemag.org/cgi/doi … 1126/science.aav9199

Journal information: Science

August 31, 2019 at 6:29 am #58977

August 31, 2019 at 6:29 am #58977

MARCH 21, 2019

New evidence links lifespan extension to metabolic regulation of immune system

by Joslin Diabetes Center

https://medicalxpress.com/news/2019-03-evidence-links-lifespan-extension-metabolic.html

Scientists have known for decades that caloric restriction leads to a longer lifespan. It has also been observed that chronic inflammation increases with age. But any relationship between the two had remained unexplored.

But in a new study, published today in Cell Metabolism, researchers at Joslin Diabetes Center have uncovered a new mechanism of lifespan extension that links caloric restriction with immune system regulation.

“Modulating immune activity is an important aspect of dietary restriction,” says Keith Blackwell, MD, Ph.D., Associate Research Director and Senior Investigator at Joslin, and Professor of Genetics at Harvard Medical School, senior author on the paper. “And it is important for longevity regulation and, in this context, increasing lifespan.”

In this study, Dr. Blackwell and his team found that caloric restriction reduces levels of innate immunity by decreasing the activity of a regulatory protein called p38, triggering a chain reaction effect ending in a reduced immune response.

Innate immunity is like the security guard of the body, keeping an eye out for any unwelcome bacteria or viruses. If the innate immune system spots something, it activates an acute immune response. We need some degree of both kinds of immunity to stay healthy, but an overactive innate immune system—which occurs more often as we age—means constant low-grade inflammation, which can lead to myriad health issues.

“[Before this study,] people looked what happens to immunity to aging in humans, but no one had ever looked in any organism at whether modulating immunity or its activities is involved in lifespan extension or can be beneficial as part of an anti-aging program,” says Dr. Blackwell.

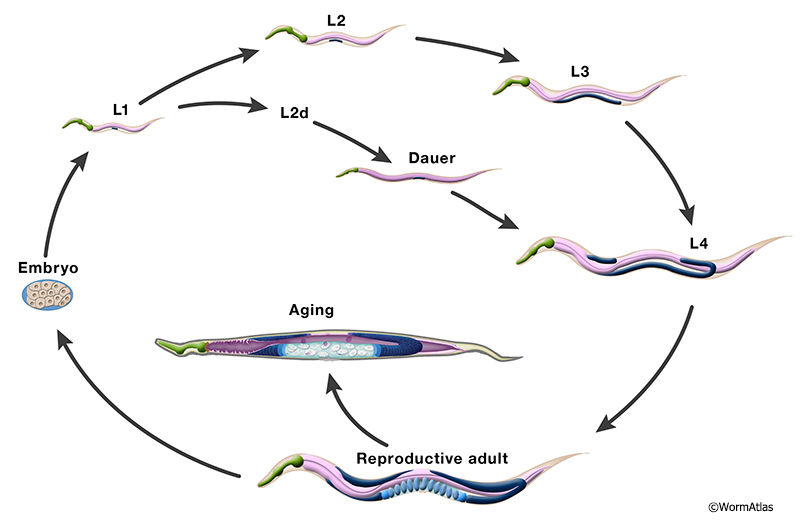

The research was conducted in the microscopic nematode worm C. elegans. The most fundamental genes and regulatory mechanisms found in these worms are typically simpler versions of those present in humans, making them a good model for studying human aging, genetics, and disease.

Dr. Blackwell and his team analyzed the levels of proteins and actions of genetic pathways during periods of caloric restriction. They were able to zero in on a particular genetic pathway that was regulated by the p38 protein. They saw that when p38 was totally inactive, caloric restriction failed and had no impact on innate immunity. When it was active, but at lower levels than normal, it triggered the genetic pathways that turned down the innate immune response to an optimal level.

“That was the most surprising thing we found. The pathway was down regulated even though it was critical,” says Dr. Blackwell.

That this immune-regulating response was activated by nutrients, rather than bacteria, was also surprising. This adds to a growing body of evidence tying metabolism to the immune system.

“This is really an emerging field in mammals now, so called immunometabolism—the idea that there are ancient links between metabolism and immunity,” says Dr. Blackwell. “We were able to show in this really very primitive immune system that it is regulated metabolically, and affects lifespan and health independently of an anti-pathogen function. That is when I started calling this a primitive immunometabolic pathway or an immunometabolic regulation.”

After making this discovery, Dr. Blackwell was curious to know if the well-known longevity mechanism of reduced IGF1 signaling also acted on the immune system. For over 20 years, study after study in many different organisms have confirmed that lower levels of IGF1 signaling contributes to a longer lifespan. This is thought to be due to the activation of protective factors by a protein called FOXO (called DAF-16 in C. elegans).

In this new study, Dr. Blackwell and his team discovered that when IGF signaling was reduced in the worms, the chain reaction set off by the FOXO-like DAF-16 not only boosted protective mechanisms, but also led to a reduction of the worms’ appetites. This naturally put the subjects in a state of caloric restriction.

“This links the growth mechanism [of IGF1 signaling] to food consumption and food seeking behavior in a big way,” says Dr. Blackwell.

A reduction in the activity of the FOXO-like gene seems to tell the worms that they are in a fasting-like state, and that nutrients may be scarce. This directs the worms to conserve energy, leading to a reduction in food intake. This self-imposed caloric restriction then leads to the lowering of the innate immune response. Dr. Blackwell plans to further study how the FOXO protein acts to suppress appetite, and to understand whether that might eventually lead to drug development.

The genes responsible for the phenomena observed in this study are conserved in humans. This opens up the possibility of human medical applications, from optimizing the immune system to drug development for appetite control.

“The ultimate goal is to be able to manipulate healthy lifespan in a person,” says Dr. Blackwell. “Not to make people live to 120, 130, but to extend the period of healthy life. And chronic inflammation is a major factor in human aging. The hope is that some of the specific mechanisms could translate to optimizing immune function in humans during aging to enhance health in human lifespan.”

September 2, 2019 at 9:47 am #58984

September 2, 2019 at 9:47 am #58984AUGUST 28, 2019

Intermittent fasting: ‘Fast and feast’ diet works for weight loss

by Serena Gordon

https://medicalxpress.com/news/2019-08-intermittent-fasting-fast-feast-diet.html

Low-calorie diets work, but can be difficult to follow. A much simpler approach to losing weight might be to just stop eating every other day.

It’s called alternate-day fasting (ADF). As the name implies, you starve yourself by fasting one day and then you feast the next, and then repeat that pattern again and again.

In just the month-long trial of the ADF diet, study volunteers lost more than seven pounds.

That weight loss occurred even though people on the ADF diet ate about 30% more on the days they were allowed to eat than they normally would. Even with that extra food on feast days, the study volunteers still consumed fewer calories overall because of their fasting days, the researchers explained.

“This is an easy regimen—no calculation of calories—and the compliance was very high,” said the study’s senior author, Frank Madeo, a professor of molecular biology at Karl-Franzens University of Graz, in Austria.

Madeo said the researchers didn’t study how the ADF diet might compare to other types of intermittent-fasting diets or to a more typical lower-calorie diet. He said that the ADF study didn’t appear to have any impact on the immune system (at least in this short-term study), but that diets that simply rely on lower caloric intake may dampen immune system function.

“The reason might be due to evolutionary biology,” Madeo suggested. “Our physiology is familiar with periods of starvation followed by food excesses.” It’s only in recent history that humans have had such an abundance of food that they need to restrict calories to maintain weight, he added.

Intermittent-fasting diets have gotten a lot of attention in the past few years. A number of celebrities, like Beyonce and Jimmy Kimmel, are rumored to use intermittent fasting to lose weight.

There are a number of variations for fasting besides ADF. Some people eat as usual for a set number of days per week, and then may fast or eat very little during the rest of the week. Some people restrict the number of hours they eat in the day, eating only from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., as an example.

That kind of diet worked for Jared Sklar, 27, of Woodland Hills, Calif. He went from 285 pounds before an intermittent-fasting diet to 190 pounds seven months later. Sklar told CNN that he only eats between the hours of 12 p.m. to 8 p.m. each day—leaving the next 16 hours as a fast. He also started eating healthier and exercising.

“There’s always something in front of me to keep me motivated, to make sure that I don’t fall back into my old habits,” Sklar said.

In the new study, Madeo’s team recruited 60 people, all healthy, non-obese adults. On average, they were just slightly overweight at the start of the study.

Half of the study volunteers relied on an every-other-day fasting plan for a month. So, in a 48-hour period, they only ate during a 12-hour period. Eating during this time wasn’t restricted.

The other 30 people ate as they normally did without any restrictions.

Folks in the “fast and feast group” lost an average of 4.5% of their body weight. The group eating normally went up an average of less than a half pound.

In addition to losing weight, the fast and feast group also saw healthy changes in heart disease risk factors, such as lower cholesterol, according to the study authors.

Despite these positive findings, the researchers aren’t yet recommending ADF diets for everyone because the long-term effects of this diet aren’t known.

Registered dietician Samantha Heller from NYU Langone Health in New York City said that although people lost weight, a diet where you fast every other day would be difficult to maintain.

“What if you want to exercise? What if you have a physically active job? Our bodies are OK with not eating for a while, but they’re happier when we have a consistent source of healthy foods to provide nutrients needed to accomplish the tasks we challenge our bodies with every day,” she said.

Plus, Heller added that it’s important to learn how to improve your lifestyle. “Someone who loses weight by fasting every other day won’t learn strategies for living a healthy life. You need to create a healthy eating pattern that you can live with.”

One simple change people can make would be to extend the natural intermittent fast everyone already does while they sleep. “For many people, after dinner is when they sit in front of the computer or TV and snack. So, close the kitchen after dinner,” she suggested.

The study was published online Aug. 27 in Cell Metabolism.

September 7, 2019 at 5:16 am #59008What can worms tell us about human aging?

FEBRUARY 6, 2019

by Babraham Institute

What can worms tell us about human ageing? A lot more than you’d think; as research led by the Babraham Institute but involving researchers from multiple disciplines drawn together from across the world has shown. In a cluster of papers, the latest of which is published today in Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, the researchers describe how a collaborative effort has developed a single agreed model of metabolic flux in a tiny worm called C. elegans, and how Babraham Institute researchers have used this model to understand more about the link between metabolism and ageing.

Metabolism fuels life; converting food to energy for cellular processes and ensuring a supply of building blocks to meet the organism’s needs. Importantly, metabolism plays a key role in modulating longevity, as many of the genes that are known to extend lifespan do so by altering the flow of energy and signals in cells and across tissues. There is demonstration of this relationship shown by the influence of diet and severe calorie restriction on lifespan in many organisms, including humans.

C. elegans is one of the best model organisms to investigate the process of ageing because of its short lifespan (2-3 weeks) and readily available genetic tools. It also shares many of its core metabolic pathways with humans and many of the key genetic players in determining the lifespan of worms have been found to do the same in humans.

“One major barrier for fully exploiting the potential of C. elegans as a research toolwas the lack of a model uniting everything that was known about C. elegansmetabolism,” says Janna Hastings, a Ph.D. student in the Casanueva lab at the Babraham Institute. “To overcome this, we initiated a global team effort to reconcile existing and conflicting information on metabolic pathways in C. elegans into a single community-agreed model and launched the resulting WormJam resource in 2017.”

The Casanueva lab at the Babraham Institute use C. elegans to understand how metabolism changes during the normal course of ageing and how a variety of interventions that change metabolic fluxes can extend the length and quality of life. Physical changes evident in ageing worms point towards the loss of central metabolic capabilities as the worms age. The developed metabolic model was valuable to their research but had one key limitation; it best reflected what was happening during the growing phase of C.elegans, not the ageing phase.

“One of the key challenges that we face when studying ageing is that the modelling tools available are optimised for animals or cells that are in the process of growing, which is not happening in aged animals,” explains Dr. Olivia Casanueva, group leader in the Epigenetics programme at the Babraham Institute.

Confronted with this challenge, the researchers re-optimised the modelling tool using data from multi-omic sources (both transcriptomics and metabolomics) and were able to adapt the tool to study metabolic fluxes during ageing.

The relevance of the model to understanding the metabolic changes that occur during ageing was validated in the lab by studying ageing worms. The research identified a number of metabolites that significantly change with age and revealed a drop in mitochondrial function with age.

Mitochondria are the powerhouse of energy production in the cell and their declining function in older humans may be central to ageing and many age-related diseases such as Alzheimer’s. The researchers asked whether the new optimised tools could predict which metabolites produced by the mitochondria might be most affected by age.

“The model prediction was quite accurate, as it predicted that Oxaloacetate, a key resource for the production of energy, was becoming limiting in aged worms,” said Dr. Casanueva. “We know that of all metabolites that can be supplemented to the food source for ageing worms, Oxaloacetate is the one metabolite that produces the most robust effect—extending lifespan by up to 20%.”

So, what can worms tell us about human ageing? A lot more now, thanks to the WormJam model and the subsequent development to adapt this for ageing studies.

“This re-optimisation of the model for ageing animals represents a significant technical advance for the field and will allow more accurate predictions of metabolic fluxes during the course of ageing,” concludes Dr. Casanueva. “By developing our understanding of the experimental model of ageing, we can gain valuable insight into what’s happening in humans—taking a step towards achieving healthier ageing.”

More information: Janna Hastings et al, Multi-Omics and Genome-Scale Modeling Reveal a Metabolic Shift During C. elegans Aging, Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences (2019). DOI: 10.3389/fmolb.2019.00002

Related publications:

Michael Witting et al. Modeling Meets Metabolomics—The WormJam Consensus Model as Basis for Metabolic Studies in the Model Organism Caenorhabditis elegans, Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences (2018). DOI: 10.3389/fmolb.2018.00096

Janna Hastings et al. Flow with the flux: Systems biology tools predict metabolic drivers of ageing in C. elegans, Current Opinion in Systems Biology (2018). DOI: 10.1016/j.coisb.2018.11.005

November 13, 2019 at 11:30 am #59501

November 13, 2019 at 11:30 am #59501 -

AuthorPosts

You must be logged in to reply to this topic.